Public Benefits Delivery & Consumer Protection

By the CFPB Office of Community Affairs – MAR 01, 2023

Cash assistance predominantly flows to low-income families in need or individuals at a precarious time. Given the often-acute needs of the populations who receive and rely on cash assistance, it is critical that beneficiaries have full and timely access to these funds. This Issue Spotlight explores the challenges that recipients of public benefits programs offering cash assistance encounter in accessing funds through financial products or services. It also summarizes CFPB consumer complaints and the results of focus groups with cash assistance recipients. This report focuses on assistance provided on prepaid cards because of specific recurring issues we have seen arising with the provision of benefits by that method.

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

This Issue Spotlight explores the challenges that recipients of public cash assistance encounter in accessing funds through financial products or services. Cash assistance predominantly flows to low-income families in need or individuals at a precarious time.1 This includes older Americans via Social Security, low-income children and families via Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), people with disabilities via Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and people who are recently unemployed via unemployment payments. Given the often-acute needs of the populations who receive and rely on cash assistance, it is critical that beneficiaries have full and timely access to these funds.

This Issue Spotlight analyzes the structure of the delivery systems for certain public benefits programs, focusing on TANF, Unemployment programs, and various Social Security payments. It also summarizes CFPB consumer complaints and the results of focus groups with cash assistance recipients.

Cash assistance can be subject to numerous fees that cut into the amount of assistance and can be subject to inaccessible funds due to inadequate customer service. This Issue Spotlight focuses in particular on assistance provided on prepaid cards because of specific recurring issues we have seen arising with the provision of benefits by that method. More specifically,

- Consumers can be encouraged by programs to receive their cash assistance through a prepaid card provided by a particular financial institution rather than through direct deposit to an account and financial institution of their choice.

- Some prepaid card providers charge numerous fees, such as maintenance, balance inquiry, customer service, or ATM fees, that chip away at people's benefits.

- Inadequate customer service from prepaid card providers means that a single problem, such as unauthorized charges on a card, can create a cascade of problems when customer service isn’t available or responsive in a timely manner.

One barrier to reform may be the decentralized nature of public benefits programs that offer cash assistance. Many federal, state, and local entities are involved in running and overseeing these programs. Each program, whether administered by federal or state government, sets up its own system for paying out cash assistance. This decentralized system leaves programs largely unaware of the features of products for which other programs are contracting and creates inconsistencies in products.

Recipients also often have minimal choice in how they receive cash assistance. When cash assistance is provided through a government-administered prepaid card, recipients do not get to choose the specific card and are locked into a relationship with the provider selected by program administrators. Additionally, relatively few vendors participate in the market for government-administered prepaid cards. For these reasons, providers may face minimal competitive pressure from program innovation, new entrants, or customer choice, which may exacerbate or cause the issues with fees and customer service that benefits recipients face.

The CFPB will continue to monitor the practices of entities that facilitate the provision of cash assistance and take action when appropriate to protect consumers from violations of the federal consumer financial laws. We will also collaborate with federal and state agencies that administer public benefits programs to support efforts to increase competition and efficiency in the delivery of cash assistance.

Section 1: Public benefits delivery

Government entities provide cash assistance through a range of programs that were intended to serve many populations—including older adults, individuals with disabilities, people who are unemployed, and low-income families with children. Public benefits programs provide recurring or one-time cash assistance,2 “near cash,”3 or in-kind4 benefits to individuals and families.5 In this Issue Spotlight, we focus specifically on the distribution of recurring cash assistance through Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)6, unemployment compensation (“Unemployment”)7, and various Social Security payments. These programs provide cash funds to cover individuals’ essential needs, making it all the more critical that beneficiaries have full and timely access to their cash benefits.

Social Security is administered by the Social Security Administration and thus is delivered in a uniform way across the United States. In contrast, TANF and Unemployment are both administered by states (and in some cases, by county administrators), leading to significant variation in program structure and delivery. TANF’s block grant structure leaves broad discretion to states to determine eligibility criteria and benefit amount.8 Unemployment is an umbrella term referring to several programs involving cash assistance payments to individuals who have lost their job.9 Federal laws and regulations provide broad guidelines on Unemployment coverage and eligibility. State laws and regulations determine specific eligibility requirements, payment amounts, and duration. In turn, this state-based discretion has resulted in essentially 53 different program implementations, though with some commonalities across programs.10

Public cash assistance is provided by direct deposit, government-administered prepaid cards, or paper checks.11 The administrator of each program decides which of these three options to offer to recipients, subject to any relevant restrictions. One such restriction that applies to the delivery of certain public benefits is the Electronic Funds Transfer Act (EFTA), implemented through Regulation E.12 EFTA generally provides, among other things, that recipients cannot be required to establish an account with a particular financial institution as a condition of receipt of a government benefit without an alternative.13 EFTA applies to both federally-administered benefits, (including Federal needs-tested programs) as well as state and local government benefits that are not needs-tested programs.14 Accordingly, distribution of federal cash assistance—such as Social Security, Social Security Disability Insurance, Supplemental Security Income, and federal tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit or the Child Tax Credit—are subject to EFTA; recipients of cash assistance provided by these programs cannot be required to receive their funds with a specific financial institution, whether on a prepaid card or to a deposit account. Similarly, state and locally administered programs subject to EFTA include Unemployment, child support, certain prison and jail ‘‘gate money’’ benefits, and pension plan payments. In contrast, needs-tested programs administered by states to which EFTA does not apply include Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

In order for a cash assistance recipient to receive their funds through direct deposit, they must be able to provide an account and routing number for an existing bank, credit union, or prepaid card account. However, a significant number of cash assistance recipients may not be able to use this option as they lack such an account. In 2021, of the households in the United States most likely to receive cash assistance—those with incomes under $30,000—an estimated 4.1 million of them lacked a bank or credit union account (i.e., are “unbanked”).15

Another common way of distributing cash assistance is through government-administered prepaid cards. The two main types of government-administered prepaid cards are the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system and the electronic payment card (EPC) system. Benefit payments provided through EBT16 allow individuals to get their cash assistance through a network of ATMs and selected merchants that accept EBT cards, whereas EPC cards are branded as Visa or MasterCard, allowing recipients to use these cards to access cash or purchase items through any merchant that accepts those cards.17 As of July 2020, 40 states issued TANF payments via EBT, while 10 states issued TANF payments via EPC.18 To offer government-administered prepaid cards that participants can then use to make purchases and withdraw cash, program administrators contract with service providers; this market will be discussed further in Section 2.

Government-administered prepaid cards provide an important vehicle to distribute cash assistance, even in cases where it transfers only a small fraction of the overall benefits. In 2020, government-administered prepaid cards were used to distribute $409 billion in public benefits, the bulk of which was cash assistance.19 The Social Security Administration, for example, paid out approximately 4.5 percent of the Administration’s benefits on its government-administered prepaid card in 2020.20

Government-administered prepaid cards offer both advantages and disadvantages; their use can benefit government administrators and recipients alike. By reducing supplies needed and demands on employee time, cards provide cost-efficiency for administrators.21 They also present an opportunity for faster access to funds for unbanked recipients over check-cashing. However, some prepaid cards can also present substantial consumer burdens, such as costly fees to access funds, or user experience hurdles, like unresponsive customer service lines, for cash assistance recipients.

Though less frequently used, paper checks are still an option at the discretion of the agency administering public benefits. Practices vary widely from program to program. For instance, paper checks are not available to most Social Security benefits recipients.22 Further, individuals who receive Unemployment in Montana may choose to receive a paper check,23 whereas Unemployment recipients in Alabama may only receive payment by direct deposit or on their government-administered prepaid card.24 In 2020, 21 states allowed consumers to receive their TANF cash payments via paper check.25

Section 2: Barriers to accessing cash assistance

Cash assistance predominantly flows to families in need or individuals at an insecure time. Barriers to accessing that assistance, such as numerous or costly fees or inadequate customer service, can create substantial financial harm. These concerns are not limited to cash assistance provided by prepaid card, but the provision of benefits by prepaid card presents specific recurring issues. Although recipients may sometimes choose the method by which their cash assistance is delivered, in the programs the CFPB examined, recipients do not have a say in the specific prepaid card program administrators use to distribute cash assistance. This presents the potential for consumer harm because a particular prepaid card may not meet a consumer’s unique financial needs.

Fees reduce benefit amounts

Government-administered prepaid cards can have numerous or costly fees associated with their use that may exceed that of other financial products or services.26 Consumers have complained to the CFPB about service fees on their government benefits cards.27 That said, the alternatives to government-administered prepaid cards—direct deposit and paper checks—can also be a source of fees.

State agencies that offer prepaid cards execute contracts with vendors, which can represent a cost saving opportunity to states over processing paper checks repeatedly.28 The prepaid card vendors that states select earn income on cardholder29 and sometimes, interchange30 fees. This relationship structure risks potential misalignment between states’ interest in programmatic cost cutting, vendors’ interest in earning revenue, and the consumer’s desire for a safe and affordable prepaid card to meet their financial needs.

While there are potential convenience and economic advantages for recipients to using government-administered prepaid cards, those benefits may be blunted by large service fees. In 2020, for example, issuers of government-administered prepaid cards collected approximately $1.3 billion in fees.31 While this fee revenue reflects only 0.3% of the $409 billion distributed, these fees may have a significant impact on the individual consumers that pay them. Additionally, public benefits recipients may have little-to-no ability to avoid these fees due to their limited ability to choose or change their card provider; they are often locked into relationships with providers chosen by the program administrator.

Common government-administered prepaid card fees can include ATM, maintenance, balance inquiry, or customer service fees. The assessment of these fees on government-administered prepaid cards has been the subject of complaints to the CFPB, as illustrated by one consumer complaint:

“I had my unemployment compensation disbursed to the provided. Each time my benefits were debited to the account they were immediately credited back under a 'Transaction Type ' called 'RETURN UNPINNED DEPOSIT '. […] I contacted the customer service phone number for [the card] at XXXX ten times through XX/XX/XXXX- they even charged me for each phone call. There is a record of this on my statement.”32

The three largest sources of cardholder fee revenue for government-administered prepaid card providers in 2020 were ATM fees, account servicing fees, and customer service inquiry fees.33

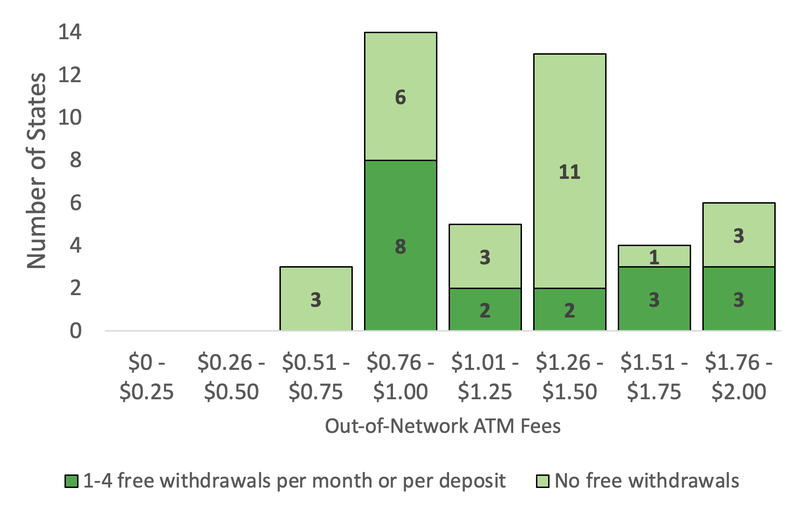

Our review of prepaid cards issued by Unemployment programs indicates that the fees for the same service vary across states, even among states that contract with the same financial institution. For instance, Unemployment prepaid card users in some states pay up to $2 for out-of-network ATM withdrawals or up to $14 for replacements cards, while recipients in other states pay nothing for those same services.34 This is also in contrast to many credit or debit card holders who pay nothing to replace a lost or stolen card.35 Figure 1 shows the variation in out-of-network fees across states. A handful of Unemployment cards also charge in-network ATM withdrawal fees, though these fees may only apply after a certain number of free in-network transactions.36 These variations in fee schedules across states and programs are dictated by the contracts signed by program administrators with financial institutions. The range of fee structures demonstrates that program administrators may have room to negotiate better prepaid card arrangements that limit costs and provide better customer service to recipients of cash assistance.

Figure 1:

Out-of-Network ATM Fees for Unemployment Insurance Prepaid Cards

Source: N=45 states' Unemployment prepaid cards. Data compiled by the CFPB.37

While Unemployment payments vary from state to state, fees on these cards can represent a significant portion of a recently unemployed consumer’s temporary cash assistance.38 Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and its ensuing additional payments, the “average weekly benefits were about $387 nationwide but ranged from a low of $215 in Mississippi to $550 in Massachusetts, and were only $161 in Puerto Rico.”39 At these payment levels, replacing a lost card can cost a recipient almost 4% of their average weekly benefit; $2 out-of-network ATM fees that may be relatively insignificant individually can accumulate to diminish cash assistance that is intended to provide financial stability to people who had been working but lost their jobs. As Unemployment replaces income for only a short period of time, the cumulative costs of those fees can place a significant burden on consumers during a period when they are already facing financial hardship. These fees may disrupt a recipient’s ability to pay their rent or mortgage, buy groceries, or purchase other necessities.

The CFPB has observed similar fee variations in the cards used to distribute TANF.40 Some of these EBT or EPC cards charge familiar fees such as out-of-network ATM withdrawal fees, but some programs’ cards charge recipients additional fees, such as a fee to check their account balance at an ATM,41 to call customer service,42 or to receive a “mobile balance alert.”43 Many TANF cards limit the number of free transactions available to users, even in network.44 Because recipients don’t have a choice in selecting the program’s prepaid products on which they receive their assistance, they may not always know what services are available to them, at what cost, or where they can access funds without incurring fees.

Individuals with minimal resources who rely on cash assistance for necessities can experience outsized harm from even low-dollar fees. In California in 2012, the ATM fees on TANF cards were estimated to total $19 million across approximately 450,000 recipient families, or approximately $43 per family per year.45 TANF provides modest payments to very low-income families, even when they receive the maximum monthly benefit, and that is important context in considering the impact of fees. These fees average out to $3.60 per month per family; while that is a low dollar amount, it could also represent, for example, a round trip fare on public transportation.46 These fees may also more acutely affect people who live in rural areas where it may be difficult to access in-network ATMs and users may be forced to incur out-of-network ATM fees, which are often substantially higher.

Inadequate customer service

Complaints to the CFPB about government-administered prepaid cards consistently reflect concerns about the adequacy of customer service. At its core, a functioning customer service system ensures consumers can fully utilize their funds. Full utilization includes an ability to rectify any problems with their government-administered prepaid card; consumers must be able address freezes and unauthorized charges on their financial products. Issues raised by consumers include inadequate protections against unauthorized transfers, high costs to replace a card, and insufficient or hypersensitive fraud filters that cause delays and account freezing.47 These issues intersect, and then can be exacerbated by the company’s poor customer service when consumers need help to resolve any of these issues. Inadequate customer service from prepaid card providers means that if any issue with a card arises (such as a lost card or unauthorized charges), a recipient can be without benefits for weeks to months while they wait for a resolution.48

As discussed in Section 1, above, EFTA applies to the delivery of some, but not all, public benefits. Where it applies, EFTA provides specific error resolution rights and dispute procedures.49 Regardless of whether EFTA applies, prepaid card providers50 and financial institutions providing consumer financial products and services, such as government-administered prepaid cards, are subject to the Consumer Financial Protection Act (CFPA)’s prohibition on unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices.51 For example, the Bureau has addressed prohibited acts and practices under the CFPA as well as under EFTA and its implementing Regulation E related to the distribution of Unemployment cash assistance in a coordinated enforcement action with the Office of the Comptroller of Currency (OCC), through which the CFPB fined Bank of America $100 million in civil money penalties. The CFPB’s order also requires Bank of America to pay eligible consumers redress related to its violations of the CFPA and Regulation E.52

The intersecting nature of customer service obstacles are present in complaints to the CFPB. One problem, such as unauthorized charges on a card, can create a cascade of problems when customer service isn’t available or responsive in a timely manner. This dynamic is illustrated by a complaint submitted to the CFPB:

“[I] noticed my account had unauthorized transactions. I called and reported it immediately and had the card shut off and claims put in for the transactions. I was told to wait for a questionnaire to fill out …The questionnaire never arrived I called in on the morning of the XXXX and was told to type a statement and include my police report of the theft with it. I did that and faxed it to them. I called back in 8 hours later to make sure they received the fax and was told my claims had been denied.”53

In fact, some consumers describe a complete inability to reach customer service representatives.54 These challenges are illustrated by another complaint submitted to the CFPB:

“I was informed … there was a total of $ XXXX dollars taken from this account by someone other than myself. … I called number after number NO ONE ANSWERS THE PHONE,” (emphasis in original).55

Consumers receiving multiple forms of cash assistance are often asked to use several cards to access benefits, requiring them to manage their finances and fees across different platforms. This may seem to be an inefficient system, however, until benefits recipients can access customer support when an issue arises, a single, centralized card may not be ideal for the cash assistance recipient. For example, if a recipient were to have all of their benefits on a single card and they experience any issue (theft, for example), then all benefits may be cut off until the issue is resolved, which may take days, weeks, or months.

Lack of consumer choice

As a general matter, there is potential for consumer harm when cash assistance recipients do not have a meaningful choice in how they receive their payments.56 A particular product that a consumer is required to use may not meet their financial needs. Moreover, the problems described above regarding fees and customer service may be exacerbated or caused by a marketplace in which providers face minimal competitive pressure.

As discussed in Section 1, above, consumer financial protection laws require consumer choice for certain cash assistance payments. EFTA, where it applies, prohibits financial institutions or other persons from requiring consumers to receive payments on a specific prepaid card with no alternative options.57 In October 2021, the Bureau took action against prison financial services company JPay for, among other things, violating EFTA and Regulation E when consumers in certain states were required to receive a government benefit owed to them at the time of their release from prison or jail on a JPay prepaid debit card.58

Even for benefits programs protected by EFTA and Regulation E, consumers that choose to receive their benefits by prepaid card do not have a choice in which company is selected by the government to provide the card. Instead, states develop contracts with a specific provider. Consumers therefore are not able to choose a product with terms or features that meets their specific needs. Because the consumer is the end-user of the cash assistance but does not select the product for disbursement and cannot switch to a different product, providers have reduced incentives to prioritize product quality and ease of use. Moreover, there is a risk that companies will take unfair advantage of recipients who are locked into a relationship with that particular provider, such as by charging complicated or large service fees.

Although some program administrators may prioritize consumer needs in the contracting process, consumer needs are not inherently part of product selection. Further, program administrators may not be fully aware of barriers to access to funds, and they may not be able to fully account for different needs among diverse groups of consumers.

Currently, the vendor marketplace offering governments prepaid cards is limited to a small number of providers. According to the CFPB’s analysis, only six banks contract with states for Unemployment government-administered prepaid cards. While four companies were under contract to provide EBT cards to states in 2022, just two companies held more than 95% of the EBT contracts.59 Within this limited marketplace, companies may face limited competitive pressure in the contracting process even if program administrators are aware of and prioritize consumer needs. The limited provider marketplace itself may be a result of operating requirements set by program administrators and customer use case. These and other factors could place pressure on some providers to generate expected revenue.

Further, programs that technically offer a choice about how benefits may be received may fail to make the options clear to the consumer or to provide access to them.60 Where EFTA applies, under Regulation E certain disclosures about payment options are required.61 Nonetheless, one consumer complained to the CFPB about their Unemployment payments being directed to a prepaid card against their wishes:

“I never used this card because I did not request it. When I completed my initial unemployment application, I requested direct deposit. 5 weeks of unemployment insurance money totaling {$1800.00} was sent to this card. […] The [agency] when I went to their office after emailing them for months & no response to my emails only confirmed the amounts and when the money was sent each week to the card. I am frustrated that no one is doing their job.”62

Additionally, how programs present options to consumers may have a significant effect on what payment method consumers select. For example, one state includes a link to sign up for direct deposit on the login page for its prepaid card.63 Other states do not present payment alternatives as clearly or accessibly. Research shows that even minor differences in application forms and sign-up processes can have dramatic effects on people's behavior.64

Conclusion and next steps

Public benefits programs offering cash assistance provide an important financial safety net to millions of low-income families and individuals at financially precarious points in their lives. Safe and efficient delivery of these benefits is essential, as it allows individuals to effectively manage their financial lives.

Cash assistance recipients are sometimes offered—or assigned—costly or inaccessible financial products on which they receive their benefits. There are relatively few vendors in the marketplace for government-administered prepaid cards, and the consumer is the end-user of the benefits but has little-to-no input on product selection. These factors may minimize the competitive forces that can improve financial products or services. There is also a risk that companies are not motivated to improve their products because they don’t have a direct relationship with the end user consumers who are locked into a relationship with the provider selected by program administrators. These challenges ultimately undermine the financial well-being of cash assistance recipients by siphoning government funds from eligible individuals and redirecting government dollars to financial institutions.

Cash assistance recipients should be protected from financial harm just like any other consumer. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is committed to making sure entities subject to federal consumer financial laws—including those involved in the delivery of cash assistance—comply with their obligations. Specifically, the CFPB will monitor and, when appropriate, take action against entities that violate the federal consumer financial laws with respect to the delivery of cash assistance.

The CFPB is sharing this Issue Spotlight with federal and state agencies that administer public benefits programs to support efforts to increase competition or otherwise address the issues raised in this Spotlight. To ensure that cash assistance recipients get the full benefit of the funds made available to them, program administrators may want to consider changes to their benefits delivery systems to increase safety, minimize fees, improve customer service, and increase choice and competition.

Footnotes

- Public benefits programs generally use the term “cash assistance” for a narrower range of means-tested cash programs. This Issue Spotlight broadens that category to include all public benefits programs that provide cash, rather than near-cash or in-kind benefits. This Issue Spotlight analyzes recurring cash payments that fall under both social welfare and social insurance public benefits programs.

- In addition to recurring public benefits payments, even more Americans receive broad cash assistance payments during national emergencies, such as COVID Economic Impact Payments (EIP).6F Congress issued three rounds of EIP to consumers, subject to income limits: EIP1 under the CARES Act; EIP2 under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (CAA); and EIP3 under the American Rescue Plan Act. The IRS distributed these payments to consumers, based on information they provided on Federal tax returns, generally through direct deposit to their deposit accounts of record or through physical checks.

- Examples of “near cash” benefits are Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which allow discretionary spending but only on approved items at credentialed retailers, or Section 8 vouchers.

- Examples of in-kind benefits include apartments in a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-funded Housing Authority, or free Covid-19 tests distributed by the U.S. Postal Service.

- About Public Assistance, U.S. CENSUS BUREAU (OCT. 3, 2022), https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/public-assistance/about.html .

- For TANF, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provides “fixed funding for the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the territories (Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands), and American Indian tribes via a block grant. States are also required in total to contribute, from their own funds, at least $10.3 billion annually under a maintenance-of-effort (MOE) requirement,” (www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/about and https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32760.pdf ).

- CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL33362, Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits (2019), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33362 (the U.S. Department of Labor provides some funding for the joint federal-state Unemployment Compensation (UC) program).

- Administration for Children & Families, About TANF, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/about and CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL32760, The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: Responses to Frequently Asked Questions, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL32760.pdf .

- See generally CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL33362, Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits (2019), (The “cornerstone” of Unemployment is the joint federal-state unemployment compensation (UC) program. DOL funding to states also includes the federal share of Extended Benefit (EB) payments and federal loans to insolvent state UC programs). For this Issue Spotlight, “Unemployment” refers to states’ Unemployment Insurance programs. See Unemployment Insurance Fact Sheet, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/factsheet/UI_Program_FactSheet.pdf .

- CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL33362, Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits (Oct. 18, 2019) https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33362 . For example, effective and safe administration of public benefits—getting the accurate amount of cash assistance to eligible recipients—is essential to maintaining financial stability for the programs, and ultimately, for the programs’ intended beneficiaries. As such, most public benefits systems require that the potential recipient self-identify and apply for any benefits for which they believe they are eligible, with supporting documentation to demonstrate their eligibility, rather than proactively identifying eligible recipients. COVID EIP payments are one recent notable exception. They were disbursed to tax filers based on their previous year’s income level.

- Sometimes recipients may choose between all three options and for some benefits programs, options are limited. For example, paper checks are not available to most Social Security, SSI, or Veteran’s benefits recipients, see, Treasury’s Direct Express website, www.fiscal.treasury.gov/directexpress .

- Electronic Funds Transfer Act, 12 U.S.C. § 1693 et seq. (2022).

- 12 C.F.R. § 1005 (2022), accord CFPB, COMPLIANCE BULLETIN ON THE ELECTRONIC FUND TRANSFER ACT’S COMPULSORY USE PROHIBITION AND GOVERNMENT BENEFIT ACCOUNTS (Feb. 15, 2022), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/compliance/supervisory-guidance/cfpb-bulletin-2022-02-compliance-bulletin-electronic-fund-transfer-acts-compulsory-use-prohibition-and-government-benefit-accounts.

- CFPB, Compliance Bulletin on the Electronic Fund Transfer Act’s Compulsory Use Prohibition and Government Benefit Accounts (Feb. 15, 2022) [hereinafter CFPB EFTA BULLETIN], https://www.consumerfinance.gov/compliance/supervisory-guidance/cfpb-bulletin-2022-02-compliance-bulletin-electronic-fund-transfer-acts-compulsory-use-prohibition-and-government-benefit-accounts.

- 13.6 percent of households in this income group are unbanked, compared to 4.5 percent of all U.S. households. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), 2021 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households Appendix Tables (October 2022) at 9 (when asked about the main reason why unbanked households don’t have accounts, the most frequently given answer is that they do not have enough money to meet accounts’ minimum balance requirements, followed by not trusting banks in general). Some “unbanked” households may have a general-purpose reloadable prepaid card that is eligible to receive federal payments by direct deposit if certain conditions are met.

- U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, FOOD AND NUTRITION SERVICE, WHAT IS ELECTRONIC BENEFITS TRANSFER (EBT)?, www.fns.usda.gov/snap/ebt (“EBT has been the sole method of SNAP issuance in all states since June of 2004.”). While EBT is predominantly associated with the “near-cash” SNAP benefits, many states also use EBT cards to distribute cash assistance, see, e.g., www.connectebt.com/pdf/LA_Client_Brochure_v1.0_Final.pdf .

- Some states block prohibited vendors on their program’s EPC card that holds TANF funds, see, e.g., Iowa Department of Human Services FIP Electronic Access Card, https://dhs.iowa.gov/sites/default/files/Comm377.pdf ; Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) Transaction Restrictions from ebtEDGE, https://www.myflfamilies.com/service-programs/access/ebt/ebtedge-transaction-restrictions.shtml.

- Graphical Overview of State TANF Policies as of July 2020, OPRE Report 2021-147, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2022), www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Graphical%20Overview%20of%20State%20TANF%20Policies%20as%20of%20July%202020.pdf .

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Government-administered, General-use Prepaid Cards (2021), https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/government-prepaid-report-202110.pdf [hereinafter Gov’t Prepaid Cards]. The total figure captures more public benefits than those covered in this Issue Spotlight, such as SNAP and child support payments.

- 20. Soc. Sec. Admin., Fast Facts & Figures About Social Security, 2021, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/chartbooks/fast_facts/2021/fast_facts21.html#trustfunds at “General Information Trust Funds,” (the Social Security Administration paid out $1.1 trillion in benefits in 2020); Gov’t Prepaid Cards, supra note 19, at 3 (approximately $50 billion of Social Security benefits were disbursed to government-administered prepaid cards).

- Press Release, Bureau of the Fiscal Service, U.S. Treasury to "Retire" Paper Check for New Recipients of Social Security and Other Federal Benefits, Saving Taxpayers $1 Billion (Apr. 26, 2011) (“It costs 92 cents more to issue a payment by paper check than by direct deposit,”).

- See Treasury’s Direct Express website, www.fiscal.treasury.gov/directexpress .

- Claimant Handbook, Montana Dept. of Labor & Industry (Apr. 2021), https://uid.dli.mt.gov/_docs/claims-processing/claimant-handbook.pdf at 10.

- Claims and Benefits FAQ, https://labor.alabama.gov/uc/21-08%20Claims%20and%20Benefits.pdf at 5.

- Welfare Rules Database July 2020 Without Text, Urban Institute, https://wrd.urban.org/wrd/databook.cfm at Table 11.A.6. For comparison, 29 states allowed TANF payments via direct deposit.

- See, e.g., https://www.eppicard.com/fledcuiclient/pdf/FL-UI_WF_LongForm_v03_ENG-Portal.pdf (Unemployment recipients in Florida are allowed one free over-the-counter transaction a month, after which they are charged $3.00 per “teller-assisted withdrawal at Visa member bank and credit union teller windows for each deposit in a calendar month”), see also, Press Release, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, CFPB Takes Action to Halt Prepaid Card Providers Siphoning Government Benefits (Feb. 15, 2022), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-takes-action-to-halt-prepaid-card-providers-siphoning-government-benefits/ (“When companies act as gatekeepers for government benefits, they often abuse that power to extract unavoidable fees,” said CFPB Director Rohit Chopra. “Barriers to choice kill competition and can harm families who need every dollar to make ends meet.”), and see generally, JPay, LLC, 2021 C.F.P.B. 0006 (2021).

- Consumer Complaint, CFPB (Dec. 23, 2021) www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/5038353 (“There are 2 pending charges that are on my account and the merchant that the pending charges are associated has no record of these pending transactions. There is no reason for the bank to hold over 1/3 of my monthly income for no reason. When calling [card provider] I was told that if a new card was issued (for a {$13.00} charge) then the balance would be transferred to the new card and the pending charges would disappear. Once the new card arrived rather than finally being able to pay my rent…, I found a $ XXXX balance and still phantom charges.”).

- Press Release, U.S. Department of Treasury, U.S. Treasury to “Retire” Paper Check for New Recipients of Social Security and Other Federal Benefits, Saving Taxpayers $1 Billion (Apr. 26, 2011) (“It costs 92 cents more to issue a payment by paper check than by direct deposit,”).

- Gov’t Prepaid Cards, supra note 19, at 3, see also, GOVERNMENT-ADMINISTERED, GENERAL-USE PREPAID CARD SURVEY Issuer Survey, Survey Period: Calendar Year 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/files/FR3063a_government_issuer_survey_2020.pdf (“Cardholder fees” as defined by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors includes: purchase transaction, ATM, over-the-counter at-bank, account servicing, routine monthly, customer service inquiry, overdraft, penalty, and other fees that do not include interchange fees).

- 12 C.F.R. § 235.2(j) (An “Interchange transaction fee means any fee established, charged, or received by a payment card network and paid by a merchant or an acquirer for the purpose of compensating an issuer for its involvement in an electronic debit transaction”).

- Gov’t Prepaid Cards, supra note 19, at 3-4 (“Between 2019 and 2020, total cardholder fee revenue increased from $157 million to $272 million,” and “In 2020, issuers of government-administered prepaid cards reported collecting roughly $1 billion in interchange fees and roughly $272 million in cardholder fees.”). This total includes payments through programs that are outside the scope of this Issue Spotlight.

- Consumer Complaint, CFPB (Aug. 24, 2022), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/5912349.

- Gov’t Prepaid Cards, supra note 19, at 4.

- Under certain circumstances. For example, 18 cards allow somewhere between 1 and 4 free out-of-network withdrawals, but their out-of-network fees jump once they reach that maximum monthly limit for free withdrawals.

- E.g., Bank of America charges $5 per lost debit card but the fee is waived for at least four different categories of accounts at the institution, https://www.bankofamerica.com/salesservices/deposits/resources/personal-schedule-fees/ ; Chase does not mention a replacement fee in its sample Cardholder Agreement online, https://www.chase.com/content/feed/public/creditcards/cma/Chase/COL00095.pdf .

- See, e.g., https://ides.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/ides/ides_forms_and_publications/bank-charges.pdf (charges $1.40 for all ATM withdrawals, but unemployment recipients get two free in-network withdrawals per month).

- This graph captures some of the complexities of prepaid card fees, such as in-network versus out of network costs, and the variable thresholds for allowable transactions without incurring a fee.

- CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL33362, Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits (Oct. 18, 2019), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33362 (the basic program in most states provides up to 26 weeks of benefits to unemployed workers, replacing about half of their previous wages, up to a maximum benefit amount).

- Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, Policy Basics: Unemployment Insurance, www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/policybasic_introtoui.pdf .

- TANF is distributed by states and means tested, and thus not subject to EFTA.

- Prepaid Account Agreements Database, CFPB, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/prepaid-accounts/search-agreements/detail/215814/. In some instances, there may be methods by which a consumer may check their balance for free, such as, if available under their government-provided prepaid card’s contract, through an online portal.

- Prepaid Account Agreements Database, CFPB, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/prepaid-accounts/search-agreements/detail/46660/; https://www.mdhs.ms.gov/economic-assistance/tanf/way2gocard/ (charges $.75 per ATM balance inquiry but disclosure notes “This fee can be lower depending on how and where this card is used. See separate disclosure for ways to access your funds and balance information for no fee.”).

- Oklahoma Human Services, TANF State Plan 2020, https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/okdhs/documents/okdhs-pdf-library/adult-and-family-services/TANFStatePlan_2020.pdf (“$.10 per request”).

- E.g., Oklahoma Human Services, TANF State Plan 2020, https://oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/okdhs/documents/okdhs-pdf-library/adult-and-family-services/TANFStatePlan_2020.pdf .

- Andrea Luquetta, The $19 million ATM fee. How better banking services would protect our public investment in families, CA REINVESTMENT COALITION REPORT (2014).

- See generally CONG. RESEARCH SERV., RL43634, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF): Eligibility and Benefit Amounts in State TANF Cash Assistance Programs (July 22, 2014), at 17, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43634.pdf .

- See Press Release, CFPB, Federal Regulators Fine Bank of America $225 Million Over Botched Disbursement of State Unemployment Benefits at Height of Pandemic (July 14, 2022), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/federal-regulators-fine-bank-of-america-225-million-over-botched-disbursement-of-state-unemployment-benefits-at-height-of-pandemic (the impact of account freezing was particularly significant during the pandemic, when many people lost access to income during a time they may have been particularly reliant on benefits).

- See OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TREASURY, Audit Report (Mar. 26, 2014) at 22, https://oig.treasury.gov/sites/oig/files/Audit_Reports_and_Testimonies/OIG-14-031.pdf (“We noted recurring suggestions in the customer satisfaction surveys regarding eliminating fees and increasing the number of surcharge-free ATMs. Also, the survey conducted in 2012 reported that 40 percent of cardholders continued to be unaware of locations for surcharge-free ATMs.”).

- 12 U.S.C. §§ 1693c and 1693f (2022).

- See, e.g., In the Matter of: UniRush LLC and Mastercard International Incorporated, 2017-CFPB-0010 (Feb. 1, 2017).

- 12 U.S.C. §§ 5531 and 5536 (2022).

- CFPB, "Federal Regulators Fine Bank of America $225 Million Over Botched Disbursement of State Unemployment Benefits at Height of Pandemic," (July 14, 2022) (The impact of account freezing was particularly significant during the pandemic, when many people lost access to income during a time they may have been particularly reliant on benefits).

- Consumer Complaints, CFPB (Jan. 18, 2022), www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/5118159 (quote reflects spelling and grammatical corrections for clarity).

- See, e.g., Consumer Complaints, CFPB (Jan. 6, 2022), www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/5073544 (A consumer's cash assistance prepaid card was locked and when they called customer service “for a replacement…, they’re not answering the phone, same recording comes on- no help,” [quote reflects spelling and grammatical corrections for clarity]).

- Consumer Complaints, CFPB (Jan. 13, 2022), www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/5107242.

- See generally Oz Shy, Low-Income Consumers and Payment Choice, FEDERAL RESERVE BANK of ATLANTA WORKING PAPER SERIES, Feb. 2020 (Rev. Oct. 2020), https://www.atlantafed.org/-/media/documents/research/publications/wp/2020/02/20/low-income-consumers-and-payment-choice.pdf , Fernando Alvarez and David Argente, Consumer Surplus of Alternative Payment Methods: Paying Uber with Cash, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2019-96, at 2019 and Carlos Arangos, Kim Huynh, and Leonard Sabetti, Consumer Payment Choice: Merchant Card Acceptance Versus Pricing Incentives, 55 JOURNAL OF BANKING AND FINANCE 130, at 141 (2015).

- CFPB EFTA BULLETIN, supra note 14.

- JPay, LLC, 2021 C.F.P.B. 0006 (2021).

- Two vendors had one contract each with one program, leaving a marketplace where most states were choosing between one of two vendors.

- Compare NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT, TRAINING AND REHABILITATION, NEVADA UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE FACTS FOR CLAIMANTS, available at https://ui.nv.gov/PDFS/UI_Claimants_Handbook.pdf (Nevada’s claimant handbook for Unemployment seems to imply that recipients may only receive their payment on the government-provided prepaid card; there is no mention of availability of direct deposit or paper checks in the claimant handbook) with DIRECT DEPOSIT BENEFIT PAYMENT METHOD, https://www.dllr.state.md.us/employment/clmtguide/uidirectdepositoverviewflyer.pdf (in 2021, Maryland transitioned to using direct deposit from a system that required applying over the phone in order to opt out of receiving its debit card).

- C.F.R. § 1005.15(c) (where EFTA applies, the consumer must receive a statement of the consumer’s payment options before a consumer acquires a government benefit account) and C.F.R. § 1005.15(c)(2)(i) (“The disclosure must include (1) a statement that the consumer has several options to receive benefit payments, followed by a list of the options available to the consumer, and a statement directing the consumer to tell the agency which option the consumer chooses, or (2) a statement that the consumer does not have to accept the government benefit account and directing the consumer to ask about other ways to receive government benefit payments.”). See also CFPB EFTA BULLETIN, supra note 14, at 12.

- Consumer Complaint, CFPB (Aug. 26, 2022), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/consumer-complaints/search/detail/5920652.

- See e.g., Way2Go Card, https://www.goprogram.com/goedcrecipient/#/ .

- See generally Exec. Order No. 13707, 3 CFR 13707 (2016).